Hey les enfants, venez voir ça!

D'autres créatures aussi déviantes et attachantes que les Panthères roses vous sont offertes ici comme modèle. Collectionnez-les... et devenez-en!

--> LE BONOBO

--> LES TWO-SPIRITS

--> LES BONOBOS SUBSTITUENT

LE SEXE À LA VIOLENCE

Chimpanzé et bonobo se ressemblent beaucoup, mais la violence du premier fait place à une sexualité débridée chez le second. À qui l'humain ressemble-t-il le plus?

Le bonobo, un proche cousin du chimpanzé, est connu depuis 1929, mais n'a été étudié sur le terrain que depuis les années 70. Cet animal étonnamment proche de nous a révolutionné la perception qu'ont les primatologues des origines de l'humanité. Alors que les chimpanzés règlent leurs conflits par la violence, les bonobos, eux, ont recours à une sexualité parfois débridée pour les résoudre. Dès lors, les primates, dont l'homme, n'apparaissent plus comme des créatures condamnées aux luttes de pouvoir.

Les chimpanzés forment une société dominée par les mâles, contrairement à ce qui se passe chez les bonobos, où ce sont les femelles qui dominent le groupe. Les deux espèces pratiquent la chasse en groupe et le partage de la nourriture, mais seuls les chimpanzés connaissent des affrontements politiques et même une forme primitive de guerre.

C'est que chez les bonobos, le sexe se substitue à l'agressivité. Tant les mâles que les femelles connaissent l'orgasme. Les pratiques sexuelles de ces singes étonnants comprennent des attouchements à deux ou à plus, entre partenaires de sexe opposé ou non, ainsi que le baiser sur la bouche, la masturbation, la fellation et la copulation dans toutes les positions, y compris celle du missionnaire qui est censée être le propre de l'homme...

Cette sexualité débridée, notent les primatologues, encourage le partage et sert à apaiser les tensions ou à se réconcilier. Elle permet aux bonobos de se mettre à la place de l'autre. Comparé au chimpanzé, le bonobo est un maître de la communication sociale. Son cousin ne l'emporte que dans la manipulation d'objets et dans l'orientation spatiale. Et de qui l'humain est-il le plus proche? Difficile à dire, mais l'étude du bonobo jette un curieux éclairage sur nos sociétés.

[texte écrit par Philippe Gauthier et piqué par accident sur: www.cybersciences.com]

*Sur les bonobos, lire aussi (en anglais):

Bonobo Society: Amicable, Amorous and Run by Females

Ces petits bonhommes sont en fait ni des bonhommes ni des bonnes femmes, ce sont des personnes two-spirits (ou bispirituelles). Avant que les Européens n'envahissent les Amériques, il existait dans plus d'une centaine de nations amérindiennes la possibilité d'être sans genre masculin ou féminin. Les two-spirits pouvaient être mariés aussi bien avec un homme ou une femme, ce qui donnait souvent naissance à des relations homosexuelles.

Est-ce qu'il reste aujourd'hui des traces ? En de rares endroits, des communautés autochtones persistent à défendre cet héritage culturel contre le rouleau-compresseur blanc. À Juchitan par exemple, qui représente la ville la plus densément peuplée par les Amérindiens en Amérique, la transgression des genres et de la sexualité continue. Cette ville, située dans le Sud du Mexique, est d'ailleurs réputée pour sa résistance légendaire aux invasions extérieures -des Espagnols, des Étatsuniens, et aujourd'hui, des fonctionnaires de l'État mexicain...

*Pour plus d'infos sur les two-spirits, lire aussi (en anglais):

What are Two-Spirits/Berdaches?

Nature's raucous bestiary rarely serves up good role models for human behavior, unless you happen to work on the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange. But there is one creature that stands out from the chest-thumping masses as an example of amicability, sensitivity and, well, humaneness: a little-known ape called the bonobo, or, less accurately, the pygmy chimpanzee. Before bonobos can be fully appreciated, however, two human prejudices must be overcome. The first is, fellows, the female bonobo is the dominant sex, though the dominance is so mild and unobnoxious that some researchers view bonobo society as a matter of "co-dominance," or equality between the sexes. Fancy that.

The second hurdle is human squeamishness about what in the 80s were called PDAs, or public displays of affection, in this case very graphic ones. Bonobos lubricate the gears of social harmony with sex, in all possible permutations and combinations: males with females, males with males, females with females, and even infants with adults. The sexual acts include intercourse, genital-to-genital rubbing, oral sex, mutual masturbation and even a practice that people once thought they had a patent on: French kissing.

Bonobos use sex to appease, to bond, to make up after a fight, to ease tensions, to cement alliances. Humans generally wait until after a nice meal to make love; bonobos do it beorehand, to alleviate the stress and competitiveness often seen among animals when they encounter a source of food.

Lest this all sound like a nonstop Caligulean orgy, Dr. Frans de Waal, a primatologist at Emory University in Atlanta who is the author of "Bonobo: The Forgotten Ape," emphasizes otherwise. "Sex is there, it's pervasive, it's critical, and bonobo society would collapse without it," he said in an interview. "But it's not what people think it is. It's not driven by orgasm or seeking release. Nor is it often reproductively driven. Sex for a bonobo is casual, it's quick and once you're used to watching it, it begins to look like any other social interaction." The new book, with photographs by Frans Lanting, will be published in May by the University of California Press. In "Bonobo," de Waal draws upon his own research as well as that of many other primatologists to sketch a portrait of a species much less familiar to most people than are the other great apes -- the gorilla, the orangutan and the so-called common chimpanzee. The bonobo, found in the dense equatorial rain forests of Zaire, was not officially discovered until 1929, long after the other apes had been described in the scientific literature.

Even today there are only about 100 in zoos around the country, compared with the many thousands of chimpanzees in captivity. Bonobos are closely related to chimpanzees, but they have a more graceful and slender build, with smaller heads, slimmer necks, longer legs and less burly upper torsos. When standing or walking upright, bonobos have straighter backs than do the chimpanzees, and so assume a more humanlike posture.

Far more dramatic than their physical differences are their behavioral distinctions. Bonobos are much less aggressive and hot-tempered than are chimpanzees, and are not nearly as prone to physical violence. They are less obsessed with power and status than are their chimpanzee cousins, and more consumed with Eros.

As de Waal puts it in his book, "The chimpanzee resolves sexual issues with power; the bonobo resolves power issues with sex." Or more coyly, chimpanzees are from Mars, bonobos are from Venus. All of which has relevance for understanding the roots of human nature. De Waal seeks to correct the image of humanity's ancestors as invariably chimpanzee-like, driven by aggression, hierarchical machinations, hunting, warfare and male dominance. He points out that bonobos are as genetically close to humans as are chimpanzees, and that both are astonishingly similar to mankind, sharing at least 98 percent of humans' DNA. "The take-home message is, there's more flexibility in our lineage than we thought," de Waal said. "Bonobos are just as close to us as are chimpanzees, so we can't push them aside."

Indeed, humans appear to possess at least some bonobo-like characteristics, particularly the extracurricular use of sex beyond that needed for reproduction, and perhaps a more robust capacity for cooperation than some die-hard social Darwinists might care to admit. One unusual aspect of bonobo society is the ability of females to form strong alliances with other unrelated females. In most primates, the males leave their birthplaces on reaching maturity as a means of avoiding incest, and so the females that form the social core are knit together by kinship. Among bonobos, females disperse at adolescence, and have to insinuate themselves into a group of strangers. They make friends with sexual overtures, and are particularly solicitous of the resident females.

The constructed sisterhood appears to give females a slight edge over resident males, who, though they may be related to one another, do not tend to act as an organized alliance. For example, the females usually have priority when it comes to eating, and they will stick up for one another should the bigger and more muscular male try to act aggressively. Female alliances may have arisen to counter the threat of infanticide by males, which is quite common in other species, including the chimpanzee, but has never been observed among bonobos.

De Waal said that many men grow indignant when they learn of the bonobo's social structure. "After one of my talks, a famous German professor jumped up and said, 'What is wrong with these males?' " he recalled. Yet de Waal said the bonobo males might not have reason to rebel. "They seem to be in a perfectly good situation," he said. "The females have sex with them all the time, and they don't have to fight over it so much among themselves. I'm not sure they've lost anything, except for their dominance."

Text by Natalie Angier

Source: New York Times

More infos:

https://www.unl.edu/rhames/bonobo/bonobo.htm

--> WHAT ARE TWO-SPIRITS/ BERDACHES ?

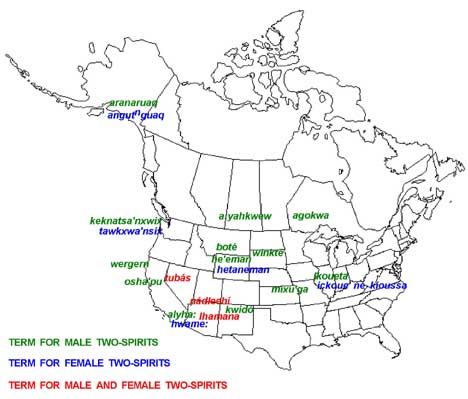

[Tribal Terms for Two-Spirit Roles]

Alternative gender roles were among the most widely shared features of North American societies. Male berdaches have been documented in over 155 tribes. In about a third of these groups, a formal status also existed for females who undertook a man’s lifestyle, becoming hunters, warriors, and chiefs. They were sometimes referred to with the same term for male berdaches and sometimes with a distinct term—making them, therefore, a fourth gender. (Thus, “third gender” generally refers to male berdaches and sometimes male and female berdaches, while “fourth gender” always refers to female berdaches.) Each tribe, of course, had its own terms for these roles, such as boté in Crow, nádleehí in Navajo, winkte in Lakota, and alyha: and hwame: in Mohave. Because so many North American cultures were disrupted (or had disappeared) before they were studied by anthropologists, it is not possible to state the absolute frequency of these roles. Those alternative gender roles that have been documented, however, occur in every region of the continent, in every kind of society, and among speakers of every major language group. The number of tribes in which the existence of such roles have been denied (by informants or outsider observers) are quite few. Far greater are those instances in which information regarding the presence of gender diversity has simply not been recorded.

“Berdache” has become the accepted anthropological term for these roles despite a rather unlikely etymology. It can be traced back to the Indo-European root *wela- “to strike, wound,” from which the Old Iranian *varta-, “seized, prisoner,” is derived. In Persia, it referred to a young captive or slave (male or female). The word entered western European languages perhaps from Muslim Spain or as a result of contact with Muslims. By the Renaissance it was current in Italian as bardascia and bardasso, in Spanish as bardaje (or bardaxe), in French as berdache, and in English as “bardash” with the meaning of “catamite”—the younger partner in an age-differentiated homosexual relationship. Over time its meaning began to shift, losing its reference to age and active/passive roles and becoming a general term for male homosexual. In some places, it lost its sexual connotations altogether. By the mid-nineteenth century, its use in Europe lapsed.

In North America, however, “berdache” continued to be used, but for a quite different purpose. Its first written occurrence in reference to third and fourth gender North American natives is in the 1704 memoir of Deliette. Eventually, its use spread to every part of North America the French entered, becoming a pidgin term used by Euro-Americans and natives alike (see Table 8.1). Its first use in an anthropological publication was by Washington Matthews in 1877. In describing Hidatsa miáti he wrote, “Such are called by the French Canadians ‘berdaches.’” The next anthropological use was in J. Owen Dorsey’s 1890 study of Siouan cults. Like Matthews, he described “berdache” as a French Canadian frontier term. Following Alfred Kroeber’s use of the word in his 1902 ethnography of the Arapaho, it became part of standard anthropological terminology.

Although there are important variations in berdache roles, which will be discussed below, they share a core set of traits that justifies comparing them:

* Specialized work roles. Male and female berdaches are typically described in terms of their preference and achievements in the work of the “opposite” sex and/or unique activities specific to their identities;

* Gender difference. In addition to work preferences, berdaches are distinguished from men and women in terms of temperament, dress, lifestyle, and social roles;

* Spiritual sanction. Berdache identity is widely believed to be the result of supernatural intervention in the form of visions or dreams, and/or it is sanctioned by tribal mythology;

* Same-sex relations. Berdaches most often form sexual and emotional relationships with non-berdache members of their own sex.

. . . In recent years, calls have been made to replace berdache with “two-spirit.” In 1993, a group of anthropologists and natives issued guidelines that formalized these preferences. “Berdache,” they argued, is a term “that has its origins in Western thought and languages.” Scholars were asked to drop its use altogether and to insert “[sic]” following its appearance in quoted texts. In its place they were encouraged to use tribally specific terms for multiple genders or the term “two-spirit.” Two-spirit was also identified as the preferred label of contemporary gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender natives.

Unfortunately, these guidelines create as many problems as they solve, beginning with a mischaracterization of the history and meaning of the word “berdache.” As a Persian term, its origins are Eastern not Western. Nor is it a derogatory term, except to the extent that all terms for nonmarital sexuality in European societies carried a measure of condemnation. It was rarely used with the force of “faggot,” but more often as a euphemism with the sense of “lover” or “boyfriend.” Its history, in this regard, is akin to that of “gay,” “black,” and “Chicano”—terms that also lost negative connotations over time.

The oft-cited 1955 article by anthropologists Angelino and Shedd has done much to perpetuate these misconceptions (and inspire attempts to find alternative terminology). The authors trace the term back to its Persian form but then state, “While the word underwent considerable change the meaning in each instance remained constant, being a ‘kept boy,’ a ‘male prostitute,’ and ‘catamite.’” This is certainly wrong. As outlined above, the meaning and use of the word underwent significant change when it was imported into Europe (where there were no “slave boys”) and even more change when it was carried to North America (where there was no tradition of age- or status-differentiated homosexuality). If the first generation of French visitors to North America used the term in a derogatory sense it soon lost this connotation as it came to be used not only as a pantribal term by natives themselves but as a personal name as well. There is no evidence that the first anthropologists to use the term were aware of its older European and Persian meanings. . . .

—from Changing Ones by Will Roscoe